Shallow Water Habitats

Ecosystem Processes - Nutrient Cycling

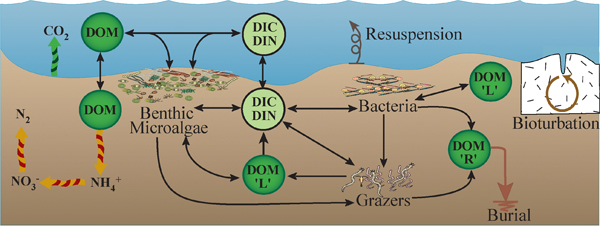

Many different nutrients are required by living organisms. These nutrients are cycled through the food web, while organic matter is being produced or degraded. Nitrogen

is an important macronutrient, which gets a great deal of attention

from estuarine scientists and resource managers because nitrogen

enrichment of estuaries and the coastal zone plays a major role in

anthropogenic (human-induced) eutrophication.

Many different nutrients are required by living organisms. These nutrients are cycled through the food web, while organic matter is being produced or degraded. Nitrogen

is an important macronutrient, which gets a great deal of attention

from estuarine scientists and resource managers because nitrogen

enrichment of estuaries and the coastal zone plays a major role in

anthropogenic (human-induced) eutrophication.

Organisms require nitrogen to form essential compounds such as amino

acids, proteins, DNA, RNA, and chlorophyll. In many coastal

environments nitrogen limits growth of phytoplankton and some nuisance

primary producers such as macroalgae. Agricultural land use is a major

source of nitrogen to the Chesapeake Bay watershed and many other

estuarine and coastal ecosystems. Other important sources include

atmospheric deposition and groundwater. When marine and estuarine

ecosystems are over-enriched with nitrogen, blooms of phytoplankton or

macroalgae may occur, which contribute to eutrophication.

Nitrogen occurs naturally in the environment in various forms,

including inorganic species, such as ammonium (NH4+), nitrate (NO3-),

nitrite (NO2-), and nitrogen gas (N2) and organic forms such as amino

acids, proteins, DNA and RNA.

Microbes, such as bacteria, are the primary mediators of nitrogen

transformations, converting inorganic nitrogen into a variety of other

inorganic or organic species. A wide variety of bacteria and some

Archaea are also responsible for converting nitrogen gas, which is

unavailable to all other forms of life, to ammonium, which can support

growth by most living organisms, a process called nitrogen fixation.

Bacteria may remove inorganic nitrogen from the environment by

denitrification or transform nitrogen into bacterial products, which

are less available to other living organisms, and which may accumulate

in the ecosystem. Primary producers also convert inorganic nitrogen

into organic matter.

Key nitrogen transformation processes are remineralization,

nitrification, denitrification, anammox, dissimilatory nitrate

reduction to ammonium, assimilation, and nitrogen fixation.

Remineralization

(or, simply, mineralization) is the breakdown of protein and other

organic matter by bacteria during respiration, which then releases

ammonium and phosphate. These are inorganic (mineral) forms.

Denitrification

is a microbially mediated anaerobic process that converts nitrate to

nitrogen gas as the final product, thereby removing it from the system

to the atmosphere. Denitrifiers use nitrate (which contains oxygen),

rather than free oxygen, to release energy from organic matter during

the process of oxidation.

Primary producers,

such as plants, trees, phytoplankton, and benthic micro- and

macroalgae, as well as bacteria and archaea take up (in a process

called assimilation) inorganic nitrogen for organic matter and biomass production.

Anammox is an anaerobic process by which bacteria ich results in the removal of nitrogen from the estuarine ecosystem.

Dissimilatory nitrate reduction to ammonium is an anaerobic process in which bacteria reduce nitrate to ammonium, a process which competes with denitrification and retains nitrogen in the ecosystem. When sulfide concentrations are high in anoxic sediment, dissimilatory nitrate reduction to ammonium is favored over denitrification.

Reducing nitrogen gas to ammonium, which is mediated by a large and diverse group of bacteria and archaea, including cyanobacteria. Nitrogen fixers make nitrogen biologically available to organisms in terrestrial and aquatic environments.For further information about nutrient cycling in estuarine and coastal marine habitats, refer to the following:

Anderson, I.C., McGlathery, K. J., and Tyler, A. C. (2003). Microbial mediation of reactive nitrogen transformations in a temperate lagoon. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 246:73-84.

Joye, S. B. and I. Anderson, 2007. Nitrogen cycling in Estuarine and Nearshore Sediments. In: Capone, D., Bronk, D., Carpenter, E. and Mulhollond, M. (Eds), Nitrogen in the Marine Environment, Springer Verlag, in press.

Mann, K. H.

2000. Ecology of coastal waters, with implications for management.

Blackwell Publishing; Chapters 2 -7 have relevant sections on nutrients

and their effects.

Munn, C. B. 2004. Marine Microbiology: Ecology and Applications. Garland Science/BIOS Scientific Publishers.

OzCoast and OzEstuaries website: http://www.ozcoasts.org.au/indicators/water_column_nutrients.jsp

http://www.ozcoasts.org.au/conceptual_mods/index.jsp

Valiela, I. 1995. Marine Ecological Processes (2nd Edition). Springer; Chapter 14 – Nutrient cycles and ecosystem stoichiometry.