East River Water Trail – Local Lore

The Mathews Maritime Heritage Trail Map not only provides an informative map for exploring the river, but also to tells the story of the people who lived and worked its shores. Some of these stories have been noted in the annals of genealogy or recounted by family members. They may be factual, supported by documentation, or interesting ephemera conveyed as family lore.

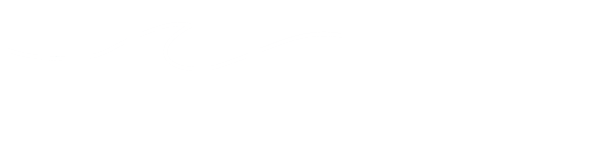

- Mobjack Bay – The large expanse of water seen when looking southeast from the Town of Mobjack is the Mobjack Bay. Said to be the most peaceful area of the Chesapeake Bay, the name Mobjack has several interpretations: One is a corruption from Algonquin Indian word meaning “ worthless earth”. A will dated July 1657 mentions “Mockjack Bay”. The most widely accepted story relates that when sailors called out over the bay, an echo would comeback from the thickly forested shoreline. They said the bay would “mock” Jack (the sailor).

- Put In Creek – It is suggested that the name originated from the story of a servant boy who was carrying a pudding to an ill lady across the creek when he slipped from the narrow footbridge and fell with the pudding into the creek. In a photocopy of a land grant patent dated 1651, from Gov. William Berkeley to William Armistead for 600 acres, the plat mentions “on the Eastward side of the Easternmost river in Mockjack Bay, beginning above Pudden Creek. Years later, the name was changed to Put-in-Creek as it sounded more genteel and boaters could “Put In” at Mathews Courthouse.

- Poplar Grove – Originally known as East Warehouse, Samuel Williams purchased the 725-acre Poplar Grove site. His sons Thomas and William Williams inherited the estate after his death. According to the Williams family tradition, however, in 1799 each son conveyed over 100 acres, including the house, to Mr. John Patterson after losing at a game of cards.

- Learning to Swim – It was important to learn to swim when transportation was by water. One story is told that children learned to swim when their father took them out in the boat and put them in the water one at a time. The watchful dad would tell the child what to do. The children learned to swim well and even the dogs and a pet pig would swim with them.

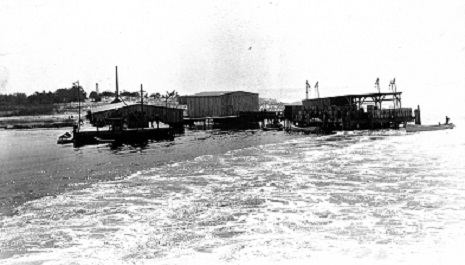

- Meeting the Steamboat – When the steamer Mobjack arrived at Philpotts Wharf, the community greeted it. Men would drive their horse and buggy to the shore where they would tie up to the rail fence. Women would be properly dressed in cotton dresses and polished buttoned shoes with their hair combed, usually sporting a hat. The folks arriving at the wharf would call the area “down to the front”

- Strange Craft – One of Captain Jeff James’ first boats was a hog trough in which he used to cross the East River when he was 8 or 10 years old. The hog trough did not go to sea, but it taught him many lessons. “It had been a considerable tree, and inside of it was dug out first to beat cider in. It held two boys,” Captain Jeff stated.

- A Ring and a Promise –Ship’s Captain Isaac Ward and shipwrights began construction of the house for himself and his fiancée Emma Forrest. He had planned for the basement, which had a dirt floor, to serve as a kitchen. Emma, born and raised in Baltimore, informed him she had no intention of cooking on a dirt floor! Construction took a turn as Isaac built onto the west side of the house two rooms for a kitchen before they were married in 1867.

- Neither Rain nor Sleet nor Snow... nor the River – Mail arriving at Williams Wharf Post Office by steamboat would be sorted and then delivered to all the wharves on the East River by boat.

- Not the Rooster’s Crow, but the Engine’s Roar – No alarm clock was needed to wake up along the East River and other shores. The sound of deadrise diesel engines starting was enough to wake a sleeping child. No grumpy children here. They understood the sound was of men going to work to feed their families.

- Ride as far as a Quarter – Susie Jarvis Brown used to walk with her mother to Hicks Wharf. From there they would take the steamboat that day and ride as far as their quarter would take them.

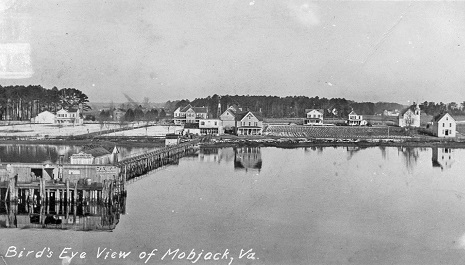

- Lumber Changed the Landscape – Lumber companies from Baltimore would hire workers to scout out good timberland and buy it for the company. “There were a lot of big trees in this county then.” Once the trees were cut they were transported to the nearest river where the logs would be put into rafts. Between 900 to 2000 logs could make up a raft, and as many as three rafts would be pulled behind a tug up the Chesapeake Bay to Baltimore. The tug would meet up with the raft at the nearest wharf to where the trees were felled. This harvesting of lumber would eventually contribute to the sedimentation of the pristine creeks and rivers.