Team encourages science-based management of shellfish diseases

Researchers at the Virginia Institute of Marine Science and the Rutgers Haskin Shellfish Research Laboratory joined with scientific colleagues, shellfish farmers, and government officials last month to explore options for improving management of oyster and clam diseases along the U.S. East Coast in light of the region’s rapidly growing aquaculture industry.

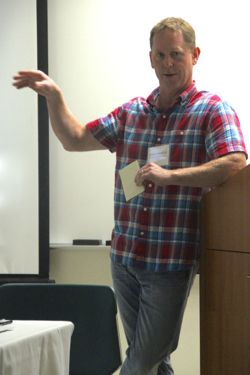

The partners met at VIMS’ Gloucester Point campus for a two-day workshop whose goal, says VIMS Research Associate Professor Ryan Carnegie, was to “identify strategies for a regional, science-based approach to shellfish management, one that facilitates interstate commerce while minimizing health risks to cultured and wild populations.” Carnegie directs the Shellfish Pathology Lab at VIMS, which performs dozens of health evaluations for industry each year.

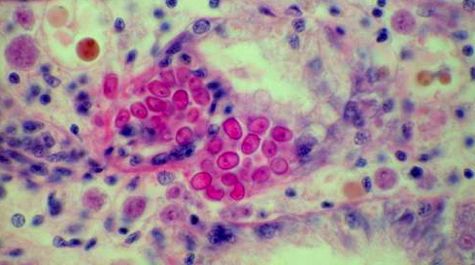

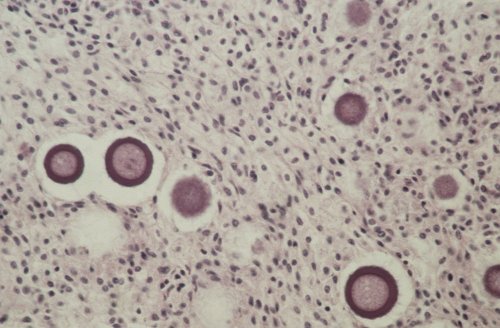

Health risks to shellfish include oyster diseases such as MSX, SSO, and Dermo; as well as the clam disease QPX. These diseases don’t affect humans, but they do threaten the health of farmed and wild shellfish, as well as the operations and profitability of shellfish growers.

Health risks to shellfish include oyster diseases such as MSX, SSO, and Dermo; as well as the clam disease QPX. These diseases don’t affect humans, but they do threaten the health of farmed and wild shellfish, as well as the operations and profitability of shellfish growers.

Carnegie co-hosted the event with Dr. David Bushek of the Haskin Shellfish Research Laboratory (HSRL) at Rutgers University, VIMS colleague Karen Hudson, New Jersey Sea Grant Aquaculture Program Coordinator Lisa Calvo, and Drs. Lori Gustafson and Lynn Creekmore of the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service Veterinary Services.

Additional participants included representatives from Cherrystone AquaFarms; the East Coast Shellfish Growers Association; the Maine Aquaculture Association; the Maryland Department of Natural Resources; the New Jersey Sea Grant Consortium; the North Carolina Division of Marine Fisheries; Oyster Seed Holdings, LLC; Roger Williams University; the Shellfish Growers of Virginia; USDA’s Agricultural Research Service; the Virginia Marine Resources Commission; and Virginia Sea Grant. Support for the workshop was provided by USDA, New Jersey Sea Grant Consortium, and Virginia Sea Grant.

Regulatory Shortcomings

“The growth of aquaculture has greatly expanded the state-to-state transport of broodstock, larvae, and seed,” says Carnegie. “That in turn has revealed shortcomings in the current regulatory framework for evaluating the health of materials proposed for interstate transfer.”

The shortcomings include serial waiting periods of at least a week—and sometimes up to three weeks—as overburdened pathology labs strive to meet the increased demand for health testing. Each test also costs several hundred to more than a thousand dollars, narrowing the profit margin for the industry’s many small growers.

A related concern, says Carnegie, is that “these costs of time and money may drive some to bypass the approval process and move seed surreptitiously, increasing the collective risk of disease introduction to the wider industry.”

Another concern, he says, is that “by focusing effort toward detecting pathogens that are widely distributed and generally manageable—Haplosporidium nelsoni and Perkinsus marinus in particular—we reduce our capacity to detect new threats that might emerge.”

Another concern, he says, is that “by focusing effort toward detecting pathogens that are widely distributed and generally manageable—Haplosporidium nelsoni and Perkinsus marinus in particular—we reduce our capacity to detect new threats that might emerge.”

H. nelsoni is responsible for MSX disease in oysters, while P. marinus causes Dermo disease. Selective breeding at VIMS and HSRL has led to farmed oysters that are relatively resistant to both diseases, while long-term field surveys at both institutions show the development of resistance in wild oysters as well. Currently, however, any sign of infection by either of these pathogens may result in the rejection of an interstate transfer request regardless of the pathogen’s natural distribution across state boundaries.

Workshop participants identified several other obstacles to effective health management for shellfish, including uncertainty regarding the geographic distribution of oyster and clam pathogens, lack of consensus regarding the levels of pathogen presence that should trigger regulatory action, and poor coordination among pathology laboratories, including little standardization of diagnostic approaches.

Participants also stressed the regulatory inconsistencies among East Coast states. VIMS’ Hudson, extension staff in the Marine Advisory Program and affiliated with Virginia Sea Grant, says the system currently in place for interstate shellfish transfers is complex and confusing. “It’s based on state boundaries rather than sound science,” says Hudson.

Proposed Solutions

There was wide agreement among meeting participants concerning areas for improvement, with several potential solutions put on the table. These include proposals to

- Develop a matrix that characterizes disease risk based on shellfish and pathogen species, geography, seed size, and other factors, and which can guide decision-making by regulators;

- Target research to address knowledge gaps in this matrix;

- Pursue hatchery certification as a means to increase the freedom to buy and sell larvae and seed not yet exposed to natural waters, which would encourage transfers of younger and more “biosecure” products;

- Promote standardization of policies through engagement with state regulatory agencies and state legislatures; and

- Promote education of growers and the public in the importance and various means of shellfish health management.

Next Steps

The dialogue will continue on January 13-14, 2015 with a larger workshop preceding the Northeast Aquaculture Conference and Exposition in Portland, Maine. This workshop, supported by a grant from NOAA’s Sea Grant Aquaculture Research Program, will bring together wide representation from industry, regulators from each East Coast state, and 14 project partners to build on progress from the VIMS workshop and define concrete steps toward solutions.

“The VIMS workshop was a start,” says Carnegie. “It jump-started the dialogue on managing disease in the context of shellfish transfers, which had gone nowhere in more than a decade. And it identified some areas in which we might make improvements or try new approaches, which we’ll talk more about in our subsequent workshop in Portland. Really, I think we’re on our way.”