Encouraging news for underwater grasses in Chesapeake Bay, despite “mystery” losses around Gunpowder and Middle Rivers

An annual survey led by VIMS researchers mapped 76,462 acres of underwater grasses in the Chesapeake Bay and its tributaries in 2022. Their report, published today, documents a 12% increase in submerged aquatic vegetation (SAV) in the regions mapped by the team, with lead researcher Dr. Christopher Patrick noting, “For the most part, we had a really encouraging year for SAV throughout the Bay.”

Underwater bay grasses are a vital part of the Bay’s ecosystem. They provide habitat and nursery grounds for fish and blue crabs, serve as food for animals such as turtles and waterfowl, clear the water by reducing wave action, absorb excess nutrients, and reduce shoreline erosion. VIMS tracks the abundance of underwater grasses as an indicator of Bay health for the Chesapeake Bay Program, the federal-state partnership established in 1983 to monitor and restore the Bay ecosystem. Using aerial surveys flown from late spring to early fall each year, VIMS researchers estimate the acreage of underwater grasses present in the Bay.

Trends in Salty and Fresh Zones

The VIMS team continued its practice— first introduced in 2013—of categorizing abundance using 4 different salinity zones, which are home to underwater grass communities that respond similarly to storms, drought, and other growing conditions.

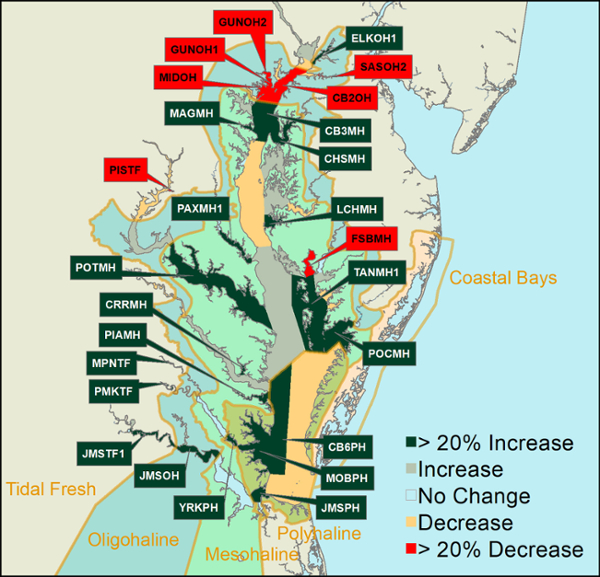

Some trends emerge across the salinity zones. Saltier areas continued to regain ground that was lost in the 2019 crash, with expansion of both eelgrass and widgeongrass. Patrick attributes this to continued nutrient management efforts and cool summers associated with La Niña. He points out that “the real test for those zones will be summer 2024 when hot summer temperatures, a known stressor of eelgrass, return with the predicted El Niño cycle.” The research team will assess those impacts, if they come to pass, in spring 2025. Grasses in the freshwater areas held nearly constant, with some areas within the zone exceeding attainment goals.

Between 2021 and 2022:

- Bay grass abundance in the Bay’s fresh waters (the Tidal Fresh Salinity Zone) fell 73 acres (from 19,179 acres to 19,106 acres).

- Bay grass abundance in the Bay’s slightly salty waters (the Oligohaline Salinity Zone) fell 1,239 acres (from 8,384 acres to 7,145 acres).

- Bay grass abundance in the Bay’s moderately salty waters (the Mesohaline Salinity Zone) increased 6,841 acres (from 24,091 acres to 30,932 acres).

- Bay grass abundance in the Bay’s very salty waters (the Polyhaline Salinity Zone) rose 2,829 acres (from 16,371 acres to 19,200 acres).

Diving Deeper: Losses in the Oligohaline Salinity Zone

In 2022, there was a significant localized decline of more than 40% around the Gunpowder and Middle rivers, which are part of the slightly salty Oligohaline Salinity Zone. According to Patrick, “Given that this loss was localized and didn’t affect segments on the western shore to the north, it’s likely caused by something happening with Gunpowder River watershed. We noted some significant turbidity spikes in the spring in that area that may have something to do with the decline. Ultimately, it’s something that demands more investigation to identify the cause to ensure it doesn’t happen again in the future.”

Absent the mysterious losses around the Gunpowder and Middle Rivers, the 2022 report would have recorded a remarkable 18% increase in Chesapeake Bay SAV prevalence.

Local Highlights

Underwater grass abundance can vary from species to species and river to river. In 2022, other local highlights included:

- Gunpowder and Middle Rivers: Roughly 1,500 acres of underwater grass were lost in Gunpower and Middle Rivers (over 40%), which accounted for 15% of the loss seen in the Bay’s Oligohaline Zone (slightly salty area). The reasons for the significant losses seen in this small area are unknown, and require further investigation by Bay scientists.

- Susquehanna Flats: The resurgence of underwater grass in the Susquehanna Flats has been occurring over the past several years, and in 2022, the segment gained another couple hundred acres.

- Tangier Sound: Both Maryland and Virginia’s portion of the Tangier Sound gained thousands of acres of underwater grass, increasing by 54%. These healthy grass beds will serve as high quality habitat for blue crabs, which is good news for crabbers working around Smith and Tangier Islands.

- Mobjack Bay to Poquoson Flats: The Mobjack Bay to Poquoson Flats, which is an area of the Bay dominated by eelgrass and widgeon grass, increased by 27%. Underwater grass abundance came close to reaching the record high from 1997.

- Pocomoke River: The lower Pocomoke River in Virginia increased by 32%, while the middle and upper parts of the river remained steady.

For a closer look at the abundance of underwater grasses, access our results. For full details, visit the SAV Monitoring & Restoration Program.