VIMS report offers mixed news on James River Kepone

Traces of toxic chemical remain four decades after spill

A recent report from the Virginia Institute of Marine Science offers mixed news concerning the persistent issue of Kepone contamination in the James River. The good news is that about a third of fish samples from the James contain no detectable trace of this now-banned pesticide; the troubling news is that two-thirds still do—more than 40 years after its discharge into the river was first reported.

The report shows that none of the fish had Kepone levels above the “action limit” established by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to control levels of contaminants in human food.

“Kepone in fish tissues has continued to decline exponentially since 1980 and should be near or below the detection limit in all samples by 2020 or 2025 if current trends continue,” says report co-author Michael Unger, an associate professor at VIMS. “But,” he adds, “the fact that 65% of fish still have reportable Kepone concentrations shows just how difficult it is to rid an ecosystem of a persistent toxic chemical.”

In a fitting note, funding for the VIMS study was provided by the Virginia Environmental Endowment, the nation’s first environmental grant-making foundation. VEE was established by court order in 1977 as part of a $13.2 million settlement with Allied Chemical Corporation, the Hopewell-based company whose improper handling of Kepone poisoned its workers and closed 100 miles of the James River to fishing for more than 10 years.

Joseph Maroon, VEE Executive Director, says “Kepone left a contamination legacy that is still around 40 years later. However, that legacy also includes the establishment of VEE, which has made more than 1,400 grants and contributed to more than $80 million in environmental improvements in the Commonwealth.”

Joseph Maroon, VEE Executive Director, says “Kepone left a contamination legacy that is still around 40 years later. However, that legacy also includes the establishment of VEE, which has made more than 1,400 grants and contributed to more than $80 million in environmental improvements in the Commonwealth.”

The report, co-authored by Unger and marine researcher George Vadas, marks the first time in almost a decade that VIMS scientists have analyzed Kepone levels in the James. “Due to state budget cuts, we hadn’t been able to monitor Kepone since 2009,” says Unger.

Maroon says "VEE was pleased—as part of its 40th-anniversary this year—to partner with VIMS to update the public on the current condition of the contaminant and to serve as a reminder to all of us for the need to avoid and prevent catastrophes like that of 40 years ago.”

For consistency, the VIMS team conducted the study using the same collection and sampling methods employed in earlier monitoring efforts, which ran annually at VIMS from 1975 to 2000, then irregularly thereafter, in 2002, 2004, 2009, and now 2016. All told, VIMS researchers have analyzed Kepone levels in more than 13,000 fish from 7 different zones in the James and Chickahominy rivers during the last 41 years.

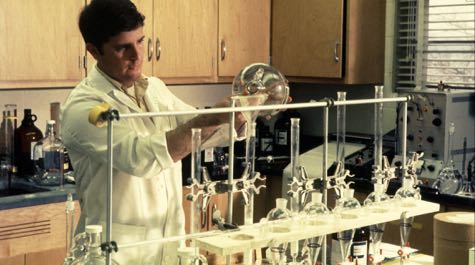

The team, which also included VIMS researcher Matt Mainor, analyzed samples from both striped bass and white perch, using a painstaking preparation technique and a gas chromatograph to accurately measure the now very low levels of Kepone in fish tissues. The fish are collected by staff with Virginia’s Department of Environmental Quality and Marine Resources Commission.

The scientists take their samples from the filet cuts typically eaten by anglers, as a way to gauge the potential health impacts to people that might regularly consume these popular recreational species. Ingestion of Kepone may lead to cancer in humans, and the workers exposed to Kepone developed severe neurologic symptoms that including tremors, altered gait, changes in behavior, weight loss, and impotence—symptoms known as the “Kepone shakes.”

In the most recent study, the VIMS team analyzed 85 samples from striped bass and white perch collected in 2016. Their results show that 35% of these samples fall below the Kepone detection limit of 0.010 parts per million, and that average concentrations now range from 0.015 to 0.030 parts per million in samples with measurable levels—well below the FDA action limit of 0.3 parts per million.

Unger calls for additional monitoring by 2025 to verify if the downward trends continue, and warns that it may be needed sooner if dredging or other activities disturb the contaminated river-bottom sediments where most Kepone now lies.

“Dredging in the James might make Kepone more available to fish and other marine life on a local basis,” says Unger, “so additional sampling might be warranted if that occurs.” He says “it’s unlikely that limited dredging would increase Kepone concentrations in fish on a prolonged basis or throughout the river like decades ago.”

Another “Kepocalypse” in our future?

The report also asks whether another Kepone-like episode could occur in Virginia’s future. Unger says the answer is “an unequivocal yes.”

“In the late ‘70s,” he says, “Virginia developed a Toxics Monitoring Program that used innovative techniques—many developed at VIMS—to look both for known toxins and unknown contaminants that might be of concern. This program discovered contaminants such as PBDEs [polybrominated diphenyl ethers] and previously unknown hotspots for PCBs and pesticides.”

In subsequent years, however, funding for the Virginia program dried up, and monitoring now focuses on specific contaminants associated with known regulatory concerns.

As a result, says Unger, “the search for unidentified, new, and emerging pollutants has faded—despite the ever-growing number of new drugs, personal-care products, and industrial chemicals entering our waters.”

Ironically, the evolution of more sensitive analytical methods adds to the problem, as this improvement has been achieved by limiting the range of detectable compounds.

“We’re now very good at quantifying what we look for,” says Unger, “but we only find what is already on a list. Untargeted contaminants are increasingly going unnoticed.”

“The results of our report underscore the need for increased support for long-term monitoring programs,” says Unger. “They’re vitally important for understanding the fate of known and emerging chemicals and their potential risks to human health and the environment.”