A great intellectual environment

The diversity of expertise at W&M’s Batten School & VIMS prepared Carole Baldwin Ph.D. ’92 for a lifelong career at the Smithsonian.

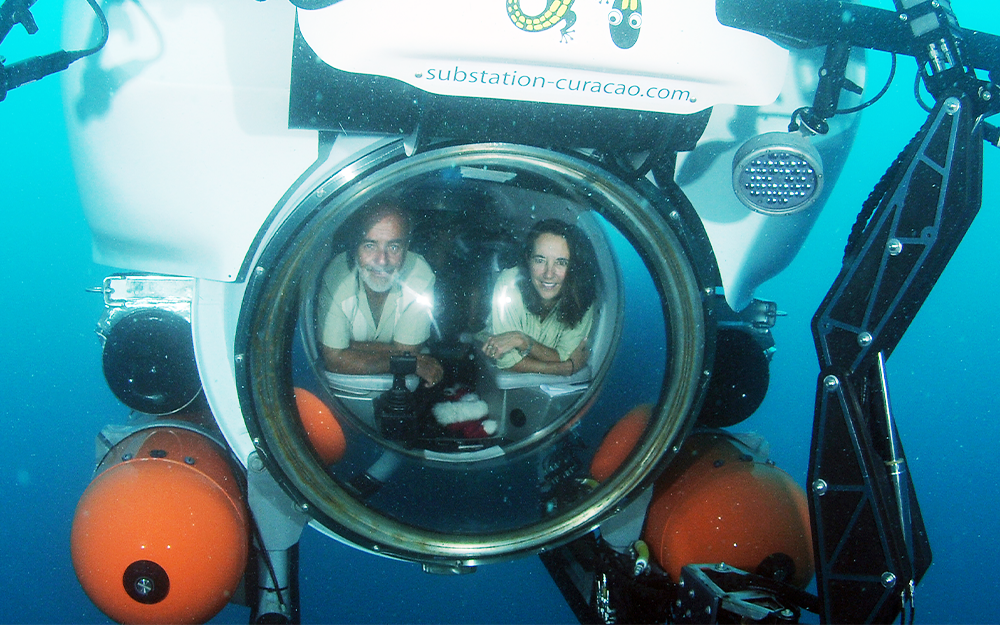

How did a post-doctoral researcher end up in an IMAX film about submersible research in the Galapagos Islands?

How did a post-doctoral researcher end up in an IMAX film about submersible research in the Galapagos Islands?

“It started over beer in the House of Blues in New Orleans,” laughed Carole Baldwin. At a conference, Baldwin was fascinated during a talk by John McCosker about ichthyology research at 3,000-foot depths. When she saw him at a subsequent reception, “I literally shook him by the shoulder and said, ‘tell me more.’”

That passion left an impression and just a few months later, when McCosker needed an extra set of hands for a research expedition that was to be documented and presented on the big screen, he called Baldwin. “Next thing I know, I'm in the Galapagos Islands," she said. “It was unbelievable. And I hate being on camera, but I said, ‘I'll do this film if you let me get in that damn sub.’ They did, and it opened my eyes to a whole new world.”

Set up for success at the “perfect” grad school

Set up for success at the “perfect” grad school

“I could have taken my marine biology career in any number of directions, but I was blown away by this fish diversity stuff,” said Baldwin, reflecting on earning her master’s degree at the College of Charleston under the tutelage of renowned ichthyologist David Johnson. Guided by that passion, Baldwin had a specific set of preferences when considering potential schools for her Ph.D.

“There were two things I wanted,” she recalled. “One, I wanted a marine science Ph.D. instead of something like evolutionary biology. Two, I wanted to be close enough to the Smithsonian to continue working with [Johnson],” who had taken a job at the National Museum of Natural History (NMNH). With an assistantship offer from longtime faculty member Jack Musick, she found that William & Mary's Batten School & VIMS — and the relatively short commute to Washington, D.C. — was “absolutely perfect.”

At the Batten School of Coastal & Marine Sciences & VIMS, Baldwin discovered a scientific environment that expanded her thinking well beyond her primary focus on fishes. “You had people interested in not just biology and biological oceanography, but also chemical, geological and physical oceanography, aquaculture and even early molecular work,” she said. “Intellectually, it was a great environment comprising a diversity of people, knowledge and expertise.” That interdisciplinary training would later prove invaluable in her career, including developing a major ocean exhibit at the NMNH.

Baldwin’s graduate research centered on larval fishes, which was an untapped area of ichthyology at the time. “Nobody had really been utilizing the larval stages of marine fishes in systematic and evolutionary studies,” she said. “The problem is identifying them, because they don't look anything like the adults; the difference can be almost as dramatic as caterpillars and butterflies.” By comparing larval and adult sea bass, Baldwin was able to demonstrate that classification using early life stages was both possible and fruitful.

Her graduate years were also marked by immersive field experiences. Baldwin served as Jack Musick’s assistant, managing preserved fish collections, teaching ichthyology labs and spending considerable time at sea. “I absolutely love being on a ship,” she said. “A lot of young people don’t get to experience living on a ship for a week or two at a time.” Those expeditions helped cement her passion for field-based marine science and reinforced the practical skills that would define her professional trajectory.

Her graduate years were also marked by immersive field experiences. Baldwin served as Jack Musick’s assistant, managing preserved fish collections, teaching ichthyology labs and spending considerable time at sea. “I absolutely love being on a ship,” she said. “A lot of young people don’t get to experience living on a ship for a week or two at a time.” Those expeditions helped cement her passion for field-based marine science and reinforced the practical skills that would define her professional trajectory.

Moving into a lifelong museum career

Five days after defending her dissertation, Baldwin began work at the Smithsonian, where she has remained ever since. Initially hired by Johnson as a postdoctoral researcher at the NMNH, she benefited from an extended period devoted almost entirely to scientific exploration. “I had no other obligations than to do research,” she said. “It was amazing.”

That period opened doors to new opportunities. Working alongside Johnson, Baldwin expanded beyond her earlier focus and began studying a wide range of fishes, including deep-sea species. Those experiences ultimately led to the IMAX film and an offer to be a full-time curator at the NMNH.

Since then, one of Baldwin’s responsibilities has been leading the Smithsonian’s Deep Reef Observation Project, a long-running effort using submersibles to explore ecosystems at depths inaccessible to conventional scuba diving. “It’s a biology bonanza,” she said, describing a zone “chock-full of unknown ocean life. I've focused on this over the last 15 years of my life, and we’ve identified about 35 new species of fish so far.”

Baldwin’s other ongoing research includes working with a team on blackwater photography and developing the first long-term dataset of temperatures on shallow-to-deep reef slopes, setting an important baseline as organisms shift their habitats in response to warming waters.

In addition to research, Baldwin has taken on significant leadership roles during her tenure at the Smithsonian, including chair of the Department of Vertebrate Zoology and interim Sant Ocean Chair. Today, her work blends research, mentorship and institutional strategy. “Helping them tease out the fun stuff, the most important stuff, the most impactful stuff — I have absolutely loved it,” she said of supporting fellow scientists.

In addition to research, Baldwin has taken on significant leadership roles during her tenure at the Smithsonian, including chair of the Department of Vertebrate Zoology and interim Sant Ocean Chair. Today, her work blends research, mentorship and institutional strategy. “Helping them tease out the fun stuff, the most important stuff, the most impactful stuff — I have absolutely loved it,” she said of supporting fellow scientists.

An alma mater connection that never fades

Baldwin remains closely connected to her alma mater through shared scientific roots with her colleagues. “The Batten School & VIMS and this museum are inextricably linked,” she proudly said, rattling off a long list of names of fellow alumni who now also work at the NMNH, which she said is often referred to as “VIMS North.”

Offering advice to students, Baldwin emphasized openness, curiosity and connection. “Get to know as many different people as you can, because there's just a smorgasbord of opportunities in terms of different kinds of research you can get involved in at the Batten School & VIMS. You don’t know how somebody’s going to influence your life.”

She also encouraged students to savor their graduate years. “Enjoy the quality time you have to devote to research while you’re in grad school,” said Baldwin. “Those are the best years ever.”