Vogelbein investigates Bermudian fish kill

VIMS professor Wolfgang Vogelbein is providing expertise to the Bermudian government concerning the cause of a recent die-off of reef fish in the waters of this small island nation.

Vogelbein, an internationally recognized expert in fish disease, was invited to the island by the Bermuda Department of Environmental Protection to determine what may have caused hundreds of dead reef fish to wash ashore in early September.

The event has now abated, and Vogelbein joined Bermudian officials in encouraging people to use common sense when it came to eating island fish, saying the majority of those caught are safe.

Bermudian scientists have suggested several causes for the fish-kill event, including excessive water temperatures, insufficient oxygen levels, increased nutrient levels, or perhaps the unusually large quantities of coral spawn seen recently.

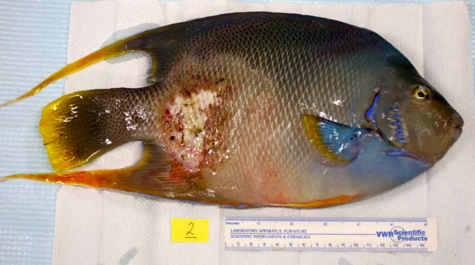

Based on his preliminary findings, Vogelbein says certain types of environmental factors likely play a role in the fish-kill, but adds that a bacterial infection also appears to be involved.

"Some of the fish have skin ulcers and others show signs of a protozoan infection in their gills," says Vogelbein. "We have been able to isolate a bacterial organism from some fish with the skin lesions."

Vogelbein suggests that a weakened immune system due to high water temperatures could be causing fish to succumb to bacteria regularly found in the ocean and not typically considered to be pathogens. "We are currently in the process of identifying the bacterial cultures and will know more soon," he said.

"These events seem to be occurring globally with greater frequency and could well be associated with rising temperatures from global warming," says Vogelbein. He notes that a similar event is now occurring in Barbados and that a massive die-off of black triggerfish occurred 2 years ago in the Maldives.

He cautions that the study may take some time to complete, due to the large number of possible underlying causes, and is thus exploring the possibility of establishing a long-term collaborative relationship with researchers at the Bermuda Department of Environmental Protection and the Bermuda Institute of Ocean Sciences.

"Everyone believes that these events will occur again," says Vogelbein, "so we're talking about the possibility of bringing a Bermudian student to VIMS for training in fish-health issues. That way, Bermuda can in time develop it's own expertise in this area. It's very likely to become a long-term collaboration."

Also involved in the study are VIMS researchers Martha Rhodes and Howard Kator, as well as Dr. David Gauthier, a 2004 graduate of the School of Marine Science at VIMS who is now a faculty member at Old Dominion University.

The current fish-kill event has only affected reef-fish such as porgies, snappers, damselfish, squirrelfish, angelfish, and parrotfish. There have been no reports of mortality among open-ocean fish, such as tuna or jacks. A similar reef-fish die-off took place in Bermuda's waters in 1997.

The island, which sits atop an extinct volcano in the otherwise deep waters of the northwest Atlantic, lies about 600 miles off Cape Hatteras. It is home to the world's northernmost coral reefs.